For another perspective on the images of Christ, read “Are Images of Christ OK? No.” by Ryan M. McGraw.

For years, Christian leaders have sounded the alarm over declining biblical literacy. In past eras, knowledge of biblical history, characters, and concepts was far more common, even among non-Christians. To make matters worse, the decline in biblical literacy is accompanied by a parallel decline in book literacy. The percentage of Americans who regularly read books of any kind (much less Scripture) is astoundingly small.

But people today aren’t dumb. Many nonreaders can talk for hours about the history, characters, and metaphysics of fictional universes like the MCU. This is a form of literacy; it just isn’t grounded in books. It’s grounded in visual media.

It’s not surprising, then, that visual adaptations of biblical stories like The Chosen have been so influential in recent years. Such works help nonreaders access biblical stories, characters, and ideas. They also prompt regular Bible readers to engage with well-known stories in fresh ways.

Throughout history (especially in premodern times), visual representations of biblical stories have fostered biblical literacy. But there’s also a long history of opposition to biblical images. This opposition is largely rooted in the belief that the second commandment prohibits visual depictions of Jesus.

Yet not all depictions of Jesus serve the same purpose. An icon, designed for veneration, doesn’t work the same way as an illustrated Bible storybook or a biblical show (like The Chosen).

As we’ll see, images of Jesus can be used to retell biblical narratives or illuminate biblical ideas without violating the second commandment, as long as they don’t divert glory away from God, distort the new-covenant story, diminish God’s nature, or deform those who use them.

Purpose of Second Commandment

When applying a biblical command to a new context, we should understand its original rationale. We mustn’t be like the Pharisees who, forgetting the purpose of Sabbath regulations, applied them in an overly broad and restrictive manner (Matt. 12:1–14). Before we can discern how to apply the second commandment to depictions of the incarnate Son of God, we need to consider its purpose.

Not all depictions of Jesus serve the same purpose.

Fortunately, the second commandment explains itself. When God prohibits graven images, he says it’s because he’s “a jealous God” (Ex. 20:5). An idol diverts glory away from the One to whom it belongs—and toward a false object. God forbids idols because he refuses to share his glory with anyone or anything—even an image that ostensibly represents him (Isa. 42:8).

Another reason God prohibits the use of graven images is because they distort the story of his relationship to Israel. When the Israelites entered into a covenant with Yahweh, they “heard the sound of words, but saw no form” (Deut. 4:12). Assigning God a form misrepresents the unique manner in which he revealed himself as King (vv. 15–18).

God also prohibits graven images because they diminish his nature and consequently deform his image-bearers. The God of the Bible is living and active. He speaks, sees, and hears for himself. He’s not a product of human hands or a mouthpiece for human agendas. It’s demeaning to identify such a God with dead wood that’s mute, blind, and deaf (Jer. 10:1–10). Moreover, because humans naturally become like what they worship, those who worship such idols eventually become spiritually disabled (Ps. 135:16–19). Instead of guiding worshipers in the ways of the living God, idols lead us into impotence and death.

But What About Images of Christ?

To understand whether the creation or use of a visual representation of Jesus violates the second commandment, we must ask whether the work

- diverts glory away from God and toward a false object,

- distorts the story of God’s relationship with his people, or

- diminishes God’s nature and deforms those who use it.

While icon veneration may divert glory away from God, narrative and exegetical depictions of Jesus perform a different function. Nobody watches Oppenheimer and praises (or blames) the film for the creation of the atomic bomb. Viewers distinguish Oppenheimer the film from Oppenheimer the man. Even if they were to picture Cillian Murphy’s face when thinking of Robert Oppenheimer, they could still easily distinguish the two individuals.

In the same way, a show like The Chosen doesn’t encourage viewers to praise the show (or Jonathan Roumie, who plays Jesus) for the gift of salvation. Some Catholic viewers have treated Roumie as a mediator for their prayers, but this kind of idolatry has more to do with the Catholic doctrine of intercession than with the nature of visual media. Apart from such teaching, narrative depictions like The Chosen will point viewers to the Scriptures—and to Jesus himself.

To evaluate whether depictions of Jesus distort the story of the divine-human relationship, we must distinguish how God revealed himself while establishing the old covenant from how he revealed himself while establishing the new. Whereas Moses emphasized how God took no visible form at Sinai, the apostles insist the Word “became flesh” (John 1:14; see 1 Tim. 3:16) that they saw and touched (1 John 1:1; 2 Pet. 1:16–18). An invisible voice spoke the law of Sinai; a visible rabbi spoke the Sermon on the Mount.

Depictions of Jesus highlight a key shift in how God relates to his people through Christ. Banning all images of Jesus minimizes this shift and may inadvertently convey a docetic Christology.

An invisible voice spoke the law of Sinai; a visible rabbi spoke the Sermon on the Mount.

While some depictions exalt Jesus and help conform viewers to his image, others diminish him and deform viewers. The former are faithful to the biblical worldview (even if they embellish narrative details); the latter turn Jesus into a mouthpiece for unbiblical teachings or behaviors. These latter works are indeed demeaning idols and may mislead unwary viewers. But depictions that faithfully convey Jesus’s countercultural voice and way of life can have the opposite effect. By upholding the biblical Jesus, they draw viewers away from death and toward true life.

Opportunity for Discipleship

Visual depictions of Jesus raise complex and challenging questions. Instead of imposing an absolute prohibition against all depictions of Jesus—or accepting all depictions without question—churches must teach members how to practice discernment.

Christians must be warned about the dangers of false or idolatrous images. But we can also be encouraged to use proper depictions of Jesus for personal enrichment, discipleship, and outreach.

Is the digital age making us foolish?

Do you feel yourself becoming more foolish the more time you spend scrolling on social media? You’re not alone. Addictive algorithms make huge money for Silicon Valley, but they make huge fools of us.

Do you feel yourself becoming more foolish the more time you spend scrolling on social media? You’re not alone. Addictive algorithms make huge money for Silicon Valley, but they make huge fools of us.

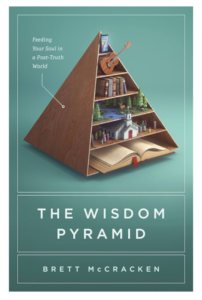

It doesn’t have to be this way. With intentionality and the discipline to cultivate healthier media consumption habits, we can resist the foolishness of the age and instead become wise and spiritually mature. Brett McCracken’s The Wisdom Pyramid: Feeding Your Soul in a Post-Truth World shows us the way.

To start cultivating a diet more conducive to wisdom, click below to access a FREE ebook of The Wisdom Pyramid.