Don Carson outlines six theological pillars for a biblical understanding of suffering.

Looking into the philosophical problem of suffering, he references David Hume’s skepticism about God’s goodness in light of pervasive hardship, and he challenges his audience to consider how to reconcile the existence of a loving, omnipotent God with the reality of suffering.

A faith that remains steadfast despite life’s trials requires a deep trust in God’s sovereignty and goodness, which can sustain believers through the deepest valleys of suffering.

Transcript

Don Carson: If you live long enough, you will suffer. If you haven’t suffered yet, you will. The only alternative is not living long enough. If you live long enough, you will be bereaved. If you live long enough, you’ll contract cancer, consumptive heart failure. You might go through a divorce. You might have a road accident or get fired from a job or two. If you live long enough, you will suffer.

If you live long enough, you’ll lose children. Almost every family lost some children 150 years ago. We don’t expect that anymore in the medicalized West. In many parts of the world, people still lose children. If you live long enough, you will lose some too. A church where I served some decades back in Canada had a woman in it who was 94 when I knew her, a widow … three times … who had lost all her children at the age of 94.

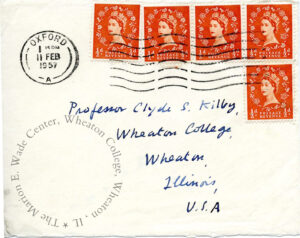

I knew a man, Norman Anderson. He eventually was knighted by the queen, so he was Sir Norman Anderson. He had been a missionary in the Muslim world and a brilliant scholar in Oriental studies. His first child was a daughter who went on to become a medical doctor and went to the Congo as a missionary as it then was, the Belgian Congo. During the upheaval in which the Belgian Congo became Zaire in 1959, she was gang raped. She was furloughed home and eventually went to California to get more medical training. She tripped, fell down some stairs, and drowned in her own spittle.

The second child died in circumstances no less bizarre. The third, who was about my age, went to Cambridge University about the time that I went, and he contracted a brain tumor and died at the age of 21 before he graduated. All three kids. I knew Norman and Pat pretty well for the next 15–20 years until they died. Not once, not once, did I ever hear him say that God wasn’t fair or complain about his loss. How do you do that? Does that even make sense?

Suffering can be a sort of theoretical problem, a kind of David Hume challenge, a skeptic from a couple centuries back. In the light of all the suffering in the world, how can God be simultaneously all powerful and good? So it’s a theoretical problem. As such, it’s something that you can knock about in a junior common room in a university or have a six-pack of beer over and argue about with a lot of one-liners in front of the tube as you’re watching a football game.

It’s when you suffer that it begins to bite. Many is the person who doesn’t even think strenuously about this subject at all until something happens to you. You may even think you have it nicely boxed and cubby-holed until your spouse comes down with an acute cancer and you watch the melanoma take them out in six weeks.

We have on our faculty a faculty member who’s been there for some time whose wife suffers from Huntington’s chorea. Of all the wretched diseases I have seen in the world, that has got to be one of the most wretched. It’s an awful disease, and each of their kids has a 50 percent chance of having the same disease. What shall we make of a tsunami that can kill 100,000? What shall we make of massive injustice, the kind of thing that you had for 15 years in southern Sudan and still have going on in southwestern Sudan in the Darfur area?

We have just come through the bloodiest century in human history. One hundred and seventy million people killed by their governments apart from war. You can actually track out these numbers on various websites. One hundred and seventy million people. More than half the population of the United States killed by their governments in the twentieth century apart from war!

You can add them all up: Close to 50 million under Mao, 20 million under Stalin in the Ukraine, 1.5 million Armenians, 1 million Hutus and Tutsis, a third of the population of Cambodia (and that’s apart from war). You just keep adding them up and adding them up. Of course, the questions about suffering and evil are asked by the Bible itself. It’s important to recognize that we do not enter this subject pressed by the circumstances of the world, but just as careful Bible readers we will come across these sorts of questions.

Read the Psalms, for example. How often does the psalmist cry to God in an agony of uncertainty because of injustice that he perceives in his own life or in the nation? There’s Jeremiah. Yes, he cannot keep quiet because the word is burning within him, but, quite frankly, he wishes God would go and take a hike somewhere so that he can get on with his life and not be constantly under the pressure of a government that is against him.

Then there’s Job. We’ll come back to him. Job doesn’t know about the first chapter, which makes it even worse. Then there’s Habakkuk. It’s comprehensible, I suppose.… Habakkuk thinks that God could use one nation to chasten another nation. It’s comprehensible. It’s a theme that you find often enough in the Bible, but how could a moral God use a more wicked regional superpower to chasten his own covenant people who by any sociological measurement is less wicked than the superpower? Habakkuk has a real tough job with that one.

Then there’s Elijah. After this massive confrontation on Carmel, he thinks that revival is right at the door, discovers instead that he’s still running for his life from Jezebel, and ends up on the backside of a desert utterly discouraged. What’s the point in all this? Then there’s the book of Revelation, with even believers under the throne already on the other side still in some sense grasping for answers. “How long, O Lord?” as they reflect on the suffering church still left behind.

Now you may think you’re going to hear three addresses on this subject. You’re not. You’re going to hear one long one. Oh, it’s divided into three parts, you know, potty breaks and that sort of thing. You must think of this as one talk. In other words, I’m not going to give you one balanced talk and then another balanced talk and then another balanced talk. I’m going to just give you one big one. So there’s a sense in which you won’t see how the parts fit together until you get the three parts together.

What I want to do in these three addresses now declared one is give you six pillars. In other words, instead of a half-dozen proof texts or a few abstract practical thoughts, I want to give you six huge theological pillars that are clearly and unambiguously taught in Scripture. Six massive pillars that together support a platform to constitute a perspective that enables you to think about these things in a biblically faithful way.

In other words, I’m not just going to give you proof texts. I’m going to give you a whole theology of suffering that is sort of reduced in the presentation to six big pillars, and if you listen only to the first pillar then you’ll be able to say to yourself again and again, “Don, you’re not being realistic. I mean what about this, what about that, and what about the other?” All I have to say is, “Hang on. There are five more pillars to go.”

You have to get all of these pillars in place before you have a platform broad enough to give you a perspective that is biblically robust and reasonably faithful. Having said all of that, at the very end I will add one more thing. Namely, that when it actually comes to helping people who are going through their worst moments a lot of it doesn’t help anyway, because when people are going through their worst moments, often they don’t want all the theology and can’t hear it. We’ll come to that this afternoon.

Often what you have to do at that point is provide a shoulder to cry on, babysitting service, and, if it’s a big disaster, helicopters and relief water and all this kind of thing. So in one sense what I’m giving you now is not designed for people who are going through the worst of it. Rather, what I’m giving you is prophylactic spiritual medicine. This is medicine you need before you get there. If you get these things truly in place in your mind, your reasoning, and your value system before you get there then you will have a stable frame of reference to handle it when you get there.

This is also medicine for somebody who has been through it and is beginning to come out the other side and is still seeing through their tears, but at least their ears are open enough now to start listening again. This might help you. Let me tell you that if you’re right in the midst of it, you might already be thoroughly ticked off by what I’ve said so far.

In other words, when you’re in the midst of it, you can be so blinded by the rage and the sorrow and the hurt that it is very, very hard to listen. I know that. In which case, listen to the recordings in six months. This is really medicine to prepare you in advance or to start giving you a biblically faithful framework after the fact. Okay, here we go. Six pillars to support a Christian worldview that enables you to think about these things in a biblically faithful and fruitful way.

1. Insights from the beginning of the Bible’s storyline

In particular, insights from Genesis 1–3 and a whole lot of text that follows from that. That is, insights from the creation and the fall. From this side of the Enlightenment, from about 1600 on, we have developed ways of thinking that try to establish proofs for the existence of God and the like.

People talked about proofs for the existence of God before that, but, from about 1600 on, Western thinkers have tried to picture human beings as independent knowers who can actually reasonably talk about whether there is enough evidence for the existence of God out there, as if we stand independently of the whole.

Interestingly enough, the Bible does not begin by saying, “Now let us consider together the possibilities of God’s existence. These are the pros, and these are the cons.” It actually just begins, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” Now if you will grant for a moment that this is true, if you will grant for a moment that God already existed before anything else did and that he has made everything, then the fact that we want to evaluate whether he exists is already an evidence of our incredible lostness.

If there had never been a fall, if God had made everything, and we, made in his image, knew him intimately, do you think we would be holding learned disquisitions on whether or not God exists? The very fact that you can start to think along those lines is already a mark, from the Bible’s point of view, of how lost and blind we already are, but the Bible just does begin with, “In the beginning God made everything.”

The reason I stress this with respect to our topic is that this helps to establish a worldview, a frame of reference, a way of looking at things. For example, in some frames of reference, in some worldviews, god and everything made are all part of the same thing. That is, god is one with everything and is the summation of it all. Somehow all of it together has a spiritual cast. Nature and the universe and everything else is all god. It’s called pantheism.

Then there’s a refinement on that that says everything that is is god, but god is not everything that is. That is, god is even bigger than everything that is, but everything that is is a big part of god, but then god is, himself, even bigger. That’s panantheism. Now if you hold either of those views, then whatever is wrong with the universe cannot be construed as the universe in rebellion against god, because this universe is god.

Then people develop new ways of analyzing what’s wrong. In some religions, for example in fact, in the form of religion that predominated in the Roman Empire from the early second century for about two and a half centuries, it was widely thought that what’s fundamentally wrong with the universe is matter. Spirit is good by definition. Matter is, at best, dicey and, at worst, actually captivating and wicked. Freedom, liberation from evil, comes by getting detached from your body. Go back to the spirit world, and everything’s hunky dory. That’s what you really need.

What’s wrong is all of this flesh, my clothes, matter, and molecules … all of that. If you can just be spiritual, then everything’s fine. That means you’re analyzing what the problem is differently from the person who thinks that God made everything good. If you read through Genesis 1 what do you see again and again? God made something or other, and he saw that it was good. Then he made something else, and he saw that it was good.

When we get down to the end of the whole creation narrative, we have, “God saw that the whole thing was good. It was very good.” In other words, the Bible doesn’t give any support for the view that matter is intrinsically bad. That’s not where the problem lies, nor does this give any credence, this biblical account, to what is often called today philosophical naturalism. This is the view that all there is is matter, energy, space, and time. That’s all there is. It’s not God. It’s just a natural world. Matter, energy, space, and time.

If you ask where it came from.… Well, the scientists are still debating. “It was the Big Bang.” Well, what caused the Big Bang? Some people think there was an expanding and contracting of everything. It went back and forth, and it keeps on going. Now there are new theories that are being developed, but, in any case, there is no place for God in this. It’s just molecules bouncing. Although there are lots of efforts to escape the entailments of that view, it’s really hard if you hold that view to say what good and bad are at all.

A couple of years ago, I was asked by CNN to be the evangelical talking head on one of the talk show programs. You know how they do this. The interviewer might be in Atlanta, the other guy on the program was in LA, and I was in Chicago. Because it had to be arranged at the last minute, they sent up a limo for me in North Chicago where I live. They normally don’t do that kind of thing, but this time they were desperate.

On the limo drive back down into town to get into the studio, I paid no attention to the driver. I was busy cramming, reading some papers so I wouldn’t look like a twit on national TV. I got down there and did my TV thing, and then I got back in the limo for the drive back home. This time, I was relaxed sitting there. “How you doing?” I was trying to chat up the driver. It turned out he was a 59-year-old Jewish man whose parents and everybody in that generation had been wiped out in the Holocaust.

We talked about this and that. It turned out he had one daughter, 33 years old. Just six weeks earlier her SUV in Kansas, in the middle of winter, had skidded and flipped, and she was now brain dead. They were just waiting to pull the plug. I said, “How’re you doing with that?” He said, “I’ve decided that the only way to think about it is, ‘Molecules bounce. It happens. Molecules bounce.’ ”

I said, “Is that the way you think about the Holocaust, too? You know, ‘Molecules bounce.’ ” Well, he was outraged, which of course is what I wanted. He was angry. “How dare you? That was Shoah. It was the worst evil. It was incredibly evil. How can you possibly say that? It was vile. It was wretched from beginning to end. It was rotten!”

I said, “So you do have a category for indignation because of moral evil after all, do you?” He said, “Are you saying that my daughter’s death is evil?” I said, “Of course that’s what I’m saying. I’m not saying that she was more evil than anybody else, but the Bible actually calls death “the last enemy.” It’s not normal. It’s disgusting. It’s a horrible thing. It’s a wretched thing. Tell me,” I said. “Would you look at death a little differently if you believed there was life on the other side?”

“Oh,” he said. “I know just what you mean. My daughter has this wonderful garden in Kansas, and I think she’d like to come back as a butterfly.” Zing. We were on different planets. You realize how worldview shapes all of your discussions. Do you see? He couldn’t be consistent. On the one hand he wanted to look at his daughter’s impending death, in order to cope with the shock and the horror and the evil of it, by saying, “Well, you know, it happens. Molecules bounce.”

But he couldn’t be consistent and say, “Well, you know, molecules bounced and they produced Hitler. Molecules bounced and they produced Auschwitz. Molecules bounced, and you have gas ovens.” You can’t do that. Somewhere along the line you’re outraged by it. Do you find that atheists or philosophical naturalists are a little more serene when it comes to injustice? Don’t they have a category for good and evil themselves, especially when it affects them? Where does this come from?

If it’s just molecules bouncing, where’s your sense of right or wrong or indignation? How can they come to Christians and start saying, “How can you believe in a God who is good and sovereign when you have all of this evil around?” Well, yes, Christians have to answer that. We’re in the process of taking one long three-part sermon to begin to get a biblical approach to it. You also have to say, “Oh, what’s your understanding?”

Because, you see, this is not just a Christian problem. For anybody who thinks, has any moral decency at all, anybody who’s made in the image of God, or anybody who is concerned about right or wrong in any sense, this is something we all have to face. I don’t care whether you’re Hindu or Muslim or an atheist, whether you’re agnostic, whether you’re a liberal or a conservative. I don’t care. Sooner or later we all have to face this kind of thing. So it’s not just a question of Christians having a dumb view versus everybody else, clearly brilliant and insightful.

What you really have to do is, in part, pitch what the Bible says about these areas against all the other views that aren’t even being faced honestly and realistically. So challenge back. Right at the very beginning of everything, you have to deal with the fact that the Bible establishes that God made everything, and he made it good.

Then we come to Genesis 3. I still often do university missions. Today in university missions the overwhelming majority of nonbelievers there are biblically illiterate. They don’t know the Bible has two Testaments. They don’t have a clue what’s going on. I often expound Genesis 3. I wish I had time now to unpack Genesis 3 for you in great detail. Let me, nevertheless, draw your attention to just a number of details, if you have your Bible.

“Now the serpent was more crafty than any of the wild animals the Lord God had made.” I’m using the NIV, and the word rendered crafty does not always get translated as crafty. The word crafty, in my ears at least, has a slightly negative overtone to it, a bit of a deceitful person, and the serpent was more deceitful. In fact, the word itself is a neutral word. Depending on the context, sometimes it just means prudent. So the serpent was more prudent? It depends on the context.

In fact, you could make a good case that God made this serpent, whatever this serpent embodies or symbolizes, with certain gifts, which when they’re corrupted become craftiness and not prudence. Now the Bible does not here spend any time in this passage explaining where the serpent came from, but it does immediately rule out one or two possibilities. We’re told right in the very first line of chapter 3, “Now the serpent was the most crafty [prudent] of all the creatures God had made.” Whoa.

Already, you do not have a competing God. You do not have a competing principle. A good God and a bad serpent, both eternal, a principle of good and a principle of evil, stretching back into eternity? No, no. The serpent belongs to the created order, although this passage does not directly describe how this serpent became the Serpent if he, too, was originally made good.

Yet there other biblical passages in 2 Peter and Jude and elsewhere that describe the angelic beings as losing their place in heaven and rebelling against God out of arrogance. It doesn’t explain how, but even there it indicates that at that order the problem is in rebellion, not in matter, for example, or not because the being is already part God.

When you read on in this passage, it’s fascinating to watch how the fall takes place. You know all of these funny little cartoons where you have sort of a line drawing, naked Adam and a naked Eve with long hair, bushes conveniently deployed so they’re not obscene, a serpent coiled on a branch, and a lovely big apple hanging down, as if God has it in for apples. He’s pretty keen on bananas and pineapples. But apples? They’re bad. You have all these cartoon figures, and the whole thing becomes a bit of a joke.

What’s going on here? The serpent’s first approach is not to deny anything. It’s to ask a question. “Did God really say you must not eat from any tree in the garden?” In other words, the Devil’s first approach is to make Eve doubt the word of God. “You mean God actually said that? You have got to be joking.” In one sense, this is slightly flattering, isn’t it? You have the capacity of standing in judgment of God. How cool is that?

Then there’s exaggeration. “Did God actually say you mustn’t eat from any tree in the garden?” God hadn’t said that. Chapter 2, verse 17 makes it clear that God had forbidden one tree and one tree only. “From all the rest you might eat.” How many were there? Hundreds? Thousands? Who knows? Lots of them. The question not only doubts what God says and his wisdom and goodness, it also portrays God as the cosmic party pooper.

“God doesn’t want you to have any fun. He doesn’t want you to eat from that tree, or that tree, or that tree, or that tree. He just doesn’t want you to do it. He’s just mean! He’s selfish and doesn’t want you to eat from the trees in the garden. That’s what God is doing. You really want to submit to that, hmm?”

That’s the implication of the question. Do you see? So that you not only stand in judgment of God in a theoretical way, but, even while you’re standing in judgment of God, you’re mentally casting an image of him as a cosmic-level party pooper, spoiling everybody’s fun.

She comes back, and, at a certain level, she starts off well. “God did not forbid all the trees in the garden.” She has that right. She’s correcting him factually. “But God did say, ‘You mustn’t eat of one particular tree in the garden. Or even touch it.’ ” No. Now she’s gone one jot too high again. God didn’t say anything about touching it.

It’s almost as if the serpent has gotten enough under her skin that she is saying, “Well, it was only one tree. Yeah, I’m not allowed to eat. I can’t even touch the thing.” So once again, you see, you’re sort of standing in judgment of God. You only begin to see how far she is beginning to slip by imagining what she should have said.

What should she have said? What she should have said is something like this, “Are you out of your little skull? I mean, give me a break. God’s the Creator. He knows what’s best. How can I possibly say what’s best? He made me. He knows how I’m wired; he did the wiring. He’s put my husband and me here in Paradise.

I mean, this is a pretty nice place, you know? I have a husband who loves me, and I love him. We walk with him in the garden in the cool.… How could you possibly suggest that I, the creature, can stand over against God in judgment of him? This is ridiculous! Get out of here.” But that’s not what she says. She begins to entertain the possibility that she can stand in judgment of God.

Thus encouraged, the Devil then makes his first explicit denial. “ ‘You will not surely die,’ the serpent said to the woman.” The first doctrine denied in all of Scripture is the doctrine of judgment. It is often the first thing to go, because if you can get rid of that one there are no sanctions, and anything else can be tamed. Worse, “For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” As is so often the case, the Devil is telling the truth and he’s telling a lie.

At the end of the chapter, God himself says that, in the wake of the sin of Adam and Eve, they have now become like us, knowing good and evil. In one sense he’s telling the truth, but he’s not telling the whole truth. The expression knowing good and evil can sometimes have the overtone in Scripture of knowing it by experience or the like. God knows the difference between good and evil because he is omniscient. They come to know the difference between good and evil by participating in the evil.

My wife has almost died twice from cancer. She does not know nearly as much about cancer as the oncologist and surgeons who have treated he, but let me tell you, she knows a lot more about cancer than any one of them from the inside. So Adam and Eve will learn about good and evil all right, but not the way God knows about good and evil from the outside, as part of the knowledge of omniscience, but rather from the inside by becoming evil. The Devil doesn’t mention that.

Moreover the expression, to know good and evil often has another overtone to it in Scripture. It means to establish good and evil, to be the being that actually sorts out what good and evil is. Now you’ve put this verse in the storyline. “God makes something, and he declares it good. Then he makes something else, and he declares it good. At the end of making everything, he declares it all very good.” It is God’s prerogative, God’s place, and God’s knowledge that declares what good is.

Now this woman is being invited, in effect, to make her own list of what’s good and evil. She will declare what’s good and evil. Now you see that this is not merely an invitation to break a rule. Though it is breaking one of the things that God prohibited, it’s more than that. It’s the beginning of all idolatry. It is to de-God God. It is to stand in God’s place. It is to be where God is and decide what good and evil is for ourselves.

The Bible then works hard all through its pages to tie all of human evil, first and foremost, to this beginning of rebellion, this initial fundamental idolatry. I wish I had time to work through the curses of this chapter, to work through the nature of death. Just remember where the Bible goes from here. I wish I had time to work through Romans 5 and how, in Adam, all of us also sin and die. I wish I had time to work through those things; I don’t.

Just remember the Bible’s storyline, for a start. The next chapter has the first murder … fratricide. The next chapter has the first lengthy genealogy, with the repeated refrain, “So-and-so lived so many years, then he begat so-and-so, then he lived so many more years, and then he died. So-and-so lived so many years, then he begat so-and-so, then he lived so many more years, and then he died. So-and-so lived so many years, then he begat so-and-so, then he lived so many more years, then he died.” It just keeps repeating, over and over again. Don’t you see? From God’s perspective, this is not the way it’s supposed to be. This is the entailment from rebellion.

Then the world is so evil that there’s judgment in the form of a flood. Noah, the preacher of righteousness, he comes out and promptly gets roaring drunk. Pretty soon the race is corrupted again, with the Tower of Babel account. God, in his mercy, decides to begin a new humanity, as it were, and calls on Abraham, from Ur of the Chaldees. He’s one of only two people in Scripture to be called a friend of God. Abraham is the father of the faithful. Great man. He’s also a filthy liar. He risks his wife … twice.

Then there’s Isaac, who’s a bit of a wimp; and Jacob, known as the deceiver; and the 12 patriarchs, with 11 of them trying to either kill or sell into the slavery the twelfth one. One of them is sleeping with his daughter-in-law. These are the patriarchs! Eventually, of course, they land up in slavery in Egypt. In due course, God raises up Moses.

Moses is a great hero, isn’t he? As a young man, he commits murder. Then when he’s an old man and God wants to use him, he does not want to go. Yes, yes, he’s praised a great deal. He’s the humblest man on the face of the earth at the age of 80. Well, you learn a few things if you survive eight decades. On the other hand, this man of great humility then loses his cool in the matter of the rock and never gets into the Promised Land.

Then they get into the Promised Land. They go through these horrible cycles of sin and degradation amongst the covenant people until the people face judgment again. Then God, in his mercy, when they cry out for help, raises up a judge, and they are restored again to strength and security. It only takes a generation or two before they slide again. These horrible cycles with the repeated refrain, “In those days, there was no king in Israel. Everyone did that which was right in his own eyes.”

Did you hear that? “Everyone did that which was right in his own eyes.” That’s called idolatry. Establishing what is right for yourself, marginalizing God, putting him off to the side, not recognizing any accountability at all, being your own god. You’re at the center of the universe. “God, how we need a king!” So they get a king. Saul doesn’t turn out too well, does he?

God graciously provides them with a David. A man after his own heart, he’s regularly called. The sweet singer of Israel. A man after his own heart … who promptly goes out and commits adultery and murder. One wonders what he would have done if he hadn’t been a man after God’s own heart.

You just keep tracking this biblical story through and through and through until you finally come to Paul saying what Paul says in Romans, chapter 1. We’ll come back to this passage a little later in the day. Let me remind you of it just the same. Chapter 1, verse 18: “The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of men who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them.”

Then you read through the next two and a half chapters. Paul’s whole point is that whether you’re a Jew or whether you’re a Gentile, whether you have revelation from God in written form or not or merely that which is stamped on the heart, none of us lives up to even what we do have. We’re a damned breed, and God does not owe us salvation.

Look at the end of this section. Chapter 3, verses 9 and following. Before one of the greatest passages on the cross in the New Testament. We’ll come back to this one later. Verse 9 of chapter 3: “What should we conclude then? Are we any better?” We Jews … are we better than Gentiles? “Not at all! We have already made the charge that Jews and Gentiles alike are all under sin. As it is written …”

Then you have this catena of biblical quotations. Listen to them. Don’t they make you uncomfortable? They just seem so over the top. Don’t they make you uncomfortable? Most of us here, if not all of us, are Christians, but they still make us uncomfortable. Imagine talking about this today in a university setting where you’re dealing with a whole lot people who don’t know anything about what the Bible says.

“As it is written: ‘There is no one righteous, not even one; there is no one who understands, no one who seeks God. All have turned away, they have together become worthless; there is no one who does good, not even one.’ ‘Their throats are open graves; their tongues practice deceit.’ ‘The poison of vipers is on their lips.’ ‘Their mouths are full of cursing and bitterness.’ ‘Their feet are swift to shed blood; ruin and misery mark their ways, and the way of peace they do not know.’ ‘There is no fear of God before their eyes.’ ”

“Oh come on, Don. It is a bit over the top, isn’t it? What about MÈdecins Sans FrontiËres, Doctors Without Borders? What about all the good things that good people do in all kinds of normal walks of life: The single mum who raises her children with courage and so on, the people who help out in all kinds of shelters and so on?” Of course there are good people around, and I’m one of them. Yet the biblical analysis, you see, is not denying any of those sociological realities.

The Bible can often speak of good and bad in certain context in those relative categories. Yet at the deepest level of analysis, we don’t know God. We run from him. We want to make our own universe. One of the most striking passages on sin that I know is Psalm 51. It’s written by David after he has committed the horrible sin regarding Bathsheba and then murdered her husband, Uriah the Hittite, and so forth. Then he’s confronted by the prophet Nathan, and he repents. There are some corporal punishments meted out. Then he pens Psalm 51.

When this is over, go back and read it. One of the things he says in the opening verses addressing God in abject repentance is: “Against you only have I sinned and done this evil in your sight.” Now at a certain level that is a load of international-class balderdash. I mean, of course he sinned against Bathsheba. He seduced her. He sinned against her husband. He cuckolded him. He sinned against the baby who was then conceived in Bathsheba’s womb.

He sinned against the military high command when he arranged that little skirmish by which Uriah the Hittite was killed. He sinned against his own family. He betrayed them. He sinned against the nation, because instead of acting as the chief justice with integrity, he’s mucking everything up. It’s hard to think of anybody who he didn’t sin against, and yet he has the cheek to say, “Against you only have I sinned and done this evil in your sight.”

Yet, at the deepest level, he has it exactly right. That is, what makes sin so vile is that it is first and foremost rebellion against God. When we who are Christians try to talk about right and wrong in the world, and when we try to justify the importance of Christians and what they do in the world, so often we’re describing things merely at a horizontal level.

You know, we Christians by and large, statistically speaking, build better homes and raise nice children and are good taxpayers and all this sort of thing. We’re honest in our dealings. That’s the ideal, at least. It’s all at the horizontal level. When you read through the Bible from the first account of sin, Genesis 3 on, what is it that most typically is said to make God angry? It’s idolatry.

The Bible says, 600 times, “God is wrathful.” Six hundred times. Overwhelmingly, he’s wrathful because of the idolatry. So that even when we’re committing these so-called horizontal sins like sleeping around, blaspheming, cheating on your income tax, cutting people off in your vehicle because you’re selfish, or whatever it is, the most offended party is always God. “Against you only have I sinned and done this evil in your sight.”

If you’re sleeping with somebody you shouldn’t be sleeping with, the most offended party is God. If you’re watching porn on the Internet, the most offended party is God. If you’re not being honest at work, the most offended party is God. That’s what makes sin, sin … because the first commandment is to love him with heart and soul and mind and strength and then our neighbor as ourselves. The second is tied to the first.

Only when we begin to absorb these kinds of things from what the Bible says, it seems to me, are we ready to face the implications of this first pillar. By and large, the biblical stance towards these things is that God doesn’t owe us anything. We’re a damned breed. He could, with perfect justice, consign all of us to perdition, and when he appears in his matchless glory we would have nothing to say.

We will then see so clearly how we have been self-focused, how we have made our own idols, how we’ve rejected the revelation that he has given. Revelation in nature; revelation in our conscience, stamped on us because we too have been made in the image of God; revelation from Holy Scripture where we’ve had access to it.

Again and again and again, by nature and by choice, we’re a damned breed, and God does not owe us anything. In fact, by and large, the Bible has not (there are some exceptions; we’ll come to them), nor have I, yet dealt with innocent suffering. We’ll come to that. There are a lot of other pillars here yet, but, by and large, the biblical stance towards these things, the first pillar to be established, is …

What’s surprising is that God hasn’t wiped us all out yet. What’s surprising is how many freedoms we enjoy, how much food we enjoy, how much of life we enjoy, how much of liberty we enjoy, how many laughs we enjoy, how much pleasantness we enjoy, how many relationships we enjoy, how many good things we enjoy considering how much our hearts are not first and foremost God-centered.

There aren’t a lot of people in the broader culture who are busy going around through life saying, “Boy, this is really enjoyable. Imagine wakeboarding for the whole weekend! Isn’t God good? We really ought to think more about God’s goodness.” Oh, I’m sure the pastor and his family.… But there are a lot of people who are wakeboarding at that same event who don’t know anything about God. They somehow think it’s their due, but if they fall and break a leg, “Damn God,” which is such an inverted attitude from the Bible’s first pillar. Do you see?

There is a remarkable passage in Luke 13:1–5. “Now there were some present at that time who told Jesus about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices.” So these are Galileans, probably Galilean Jews whom Pilate has killed for some reason not explained, and then actually took their human blood and mixed with the blood of the animals that they were sacrificing.

“Jesus answered, ‘Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans because they suffered this way?’ ” In other words, “Why do you think this happened? Because they were worse, more evil?” “No,” he says. “I tell you, unless you repent you too will all perish.”

Now in that case the suffering has come from an overt evil, Pilate’s overt evil, but the same argument holds when there are so-called natural disasters. Verse 4: “Or those eighteen who died when the Tower in Siloam fell on them—do you think they were more guilty than all the others living in Jerusalem? I tell you, no! But unless you repent, you too will all perish.”

So all the people who died in Katrina, do you think they were more evil than others? It’s so interesting to see what Jesus says. He does not say, “No, of course not. They’re fine people. It was just an accident. I mean, accidents happen. It’s sad. Maybe God was taking a walk at the time, but it happens, and they were fine people. There was no particular reason why they should die.”

That’s not what Jesus says. He says the really surprising thing is that you haven’t died, but you will. “You too will perish.” So whether Katrina takes you out now or you die in 5 years, 10 years, 20 years, or 50 years, the point is you’re still all under this curse. You’re still all under this sentence of death. That’s the assumption. Do you see? It’s a way of looking at reality that utterly blows out the first objections. So those are insights from the beginning of the Bible’s storyline. Now let me bring you some …

2. Insights from the end of the Bible’s storyline

I cannot sufficiently stress that the Bible lays out a heaven and earth to be gained and a hell to be shunned. If you try to assess what’s going in righteousness or suffering or handicap or illness or the like, only in this age.… If that is the framework in which you try to think about these things and no other, you cannot begin to make progress.

You cannot begin to do so because inevitably things will look a bit different 50 billion years from now. If you don’t believe that there’s no way this conversation can go much farther. When I was a boy we used to sing a song. It was a bit sentimental and squishy; nevertheless, it had some truth.

It will be worth it all when we see Jesus,

Life’s trials will seem so small when we see Christ;

One glimpse of His dear face all sorrow will erase,

So bravely run the race till we see Christ.

There was a time when Christians were known, in the Puritan period, as people who knew how to die well. I’d like to know how many of you are known in your communities as people who know how to die well. It was part of Christian concern to be known as people who knew how to die well.

About three years or so ago in our church there was a woman who came down with cancer. We’ll call her Mary. This was her second round. She had had cancer five years earlier, stage 0 breast cancer, the earliest, lightest form. It was judged completely handled, no ongoing chemo or the like. It was terrific. She was fine. Seven years later it came back, and it came back with a vengeance.

Now Mary was a remarkable woman. She and her husband, laypeople, had a great heart for missions. For example, they used about half the space in their basement to collect stuff for missionaries when missionaries come back. You know, they come back from who knows wherever they’ve been, and they’re going to need stuff for their six months or nine months of furlough, toasters and blankets and this and that.

She’d collect this stuff, sometimes buying it and sometimes scrounging it from Christians. She’d always say, “No junk! Missionaries deserve better than junk!” She’d collect all this stuff so that it was already there and available. She started a small business on the side and got a whole lot of women involved working virtually free so that the profits could all go into missions. She became head of her denomination’s women’s organization in the entire country.

She was a remarkable woman, and now she had cancer. She was diagnosed in May. In September, our church held a prayer meeting for her. She was so well known, although the church only had between 500 and 600 people, 287 showed up for a day-long prayer meeting for her, because they came in from churches all over the place. I wasn’t there; I was out of town. My wife went. Although this was not a church from a warm-hearted, charismatic tradition, the prayers as the days wore on were becoming progressively more enthusiastic.

“Lord, you have said that if two or three on earth be agreed as touching anything.… We have 287 here, and we’re all in agreement Lord. We want you to heal her. Lord, Jesus is still the Great Physician. He never finally turned anybody away when he was on earth, and Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever. Lord, we want you to show that you’re still the same today. We want you to heal Mary. Lord, you’ve seen all the good that she’s done. How can we possibly lose her at this stage? What will her husband and her children do?” It ratcheted up and ratcheted up and ratcheted up.

Finally, it was my wife’s turn to pray. She, who had almost lost her life twice. She said, “Dear heavenly Father, we would so much like you to heal dear Mary, but we also recognize we’re all under a curse, and if you won’t heal her until the resurrection, then teach her to die well. Plant one foot firmly in eternity. Fill her with the joy of the Lord. Give her a heritage for her husband and children so that they will remember to look to Christ. We don’t ask that she has an easy time. We ask that she’s so full of grace that people will see Christ in her. Teach her to die well.”

Well, you could have cut the air with a knife. You’re not supposed to say things like that! We were told afterwards by some of the relatives that they were rather hoping my wife would experience this first so she could know whereof she was praying. In November, her husband phoned me. “Don, I’ve got to talk to you. I’ve got to talk to you now.”

So we went out to a coffee shop. Do you know what he wanted? By this time, her health was going down and down. She’d had every treatment conceivable. She had a brain shunt in her head so they could put chemicals right into her skull. The church was wonderful at one level, bringing in food all the time. People dropping by would say, “How are you doing today, Mary?”

“Oh, it’s awful.”

“Don’t worry, we’re praying for you. The Lord is faithful to his promises.”

On and on and on. Do you know what he wanted? He wanted permission to let her die. She couldn’t focus on eternity because there were so many flipping Christians around telling her she was going to be healed. What a stupid course of events. We’re all going to die, unless the Lord comes back first. I can’t think of any exceptions in this room. Do Christians know how to die well?

In our culture, death has just about become the last taboo subject. I can get a bunch of university students in, sit them around the table, and I can get a conversation going on anything. “Hey, what do you guys think about homosexuality?” Bang! Everybody’s right in there. But if I say, “I’d like to tell you how my dad died.” Well, it’s as if I’ve committed a huge social gaffe. Everybody is deathly still. “Well, this is going to be embarrassing. Whoa.”

Christians shouldn’t be like that. Whatever else a local church jolly well had better do is prepare its members to meet God. Unless Christ comes back first, that means prepare to die. We had better be a generation that knows how to die well, for you cannot live faithfully in this life unless you’re ready for the next life. It cannot be done.

You cannot preserve morality or spirituality or doctrinal purity or faithfulness in the home, or anything else unless you’re living in the light of eternity. You cannot do it. So this stance from the end of life begins to reconfigure everything in this life, so that even if there are sorrows that we do not yet understand, one day we will stand in the presence of the King with our resurrection bodies, and we will look at everything from a slightly different angle.

We will see everything through the triumphs of Christ, and even the cancer that took us out or the suffering Christians in some godforsaken part of the world where there is constant persecution (another theme to which we will refer), where there is judgment meted out in political and sociological and disease terms.… All of those things will look very differently 50 billion years into eternity.

In other words, one of the things that Christians have to remember is that here there is no utopia. We may have our preferences in the upcoming elections. Some of us may be pretty strongly convinced one way or the other that if only this party gets in or that party gets in things will be a lot better in this country.

Boy, have I got news for you! Oh, there may be better and worse. No doubt. Here there is no utopia. None. There will not be a utopia. Oh, yes, we should pursue righteousness. Righteousness exalts the nation. Sin is a reproach to any people, but at the end of the day, until the end, there is no utopia. We live in the light of that expectation.

Let me end this first session by reminding you of something that C.S. Lewis wrote a long time ago. C.S. Lewis fought in the trenches of World War I, that most stupid and idiotic of wars. Indefensible. Inexcusable. Without reason. Without rationale. Ten million people mowed down by Howitzers and machine guns for the gain of a few hundred yards one way or the other across a 2,300-mile trench right across Europe. A stupid war with no aim and no goal except this vague thing called national honor. He saw virtually all of his friends butchered in the trenches, but he survived.

Then a bare 20 years later, World War II broke out. By this time, he was lecturing at Oxford University. The university chaplain in the university church didn’t have a clue what to say to these young men. How do you get young men to be studying in wartime when everything seems so … ultimate? What’s the point of studying microbiology and Roman history and English literature when people are mowing each other down? How do you make sense of that?

So the chaplain asked Lewis, who by this time was already beginning to establish, even as early as 1939, the beginning of a reputation for Christian apologetic. On that Sunday night, he climbed into the pulpit and gave an address that has been published many times called “Learning in Wartime.” You can find it on the Internet and you can find it in his collected essays called Fern-Seed and Elephants and Other Essays on Christianity. Let me just read you a few paragraphs.

“A university is a society for the pursuit of learning. As students, you will be expected to make yourselves, or to start making yourselves, into what the Middle Ages called clerks, into philosophers, scientists, scholars, critics, historians, and at first sight this seems to be an odd thing to do during a great war.

What is the use of beginning a task which we have so little chance of finishing? Or even if we ourselves should happen not to be interrupted by death or military service, why should we, indeed how can we, continue to take an interest in these placid occupations when the lives of our friends and the liberties of a Europe are in the balance? Is it not like fiddling while Rome burns?

Now it seems to me that we shall not be able to answer these questions until we have put them by the side of certain other questions, which every Christian ought to have asked himself in peacetime. I spoke just now of fiddling while Rome burns, but to a Christian the true tragedy of Nero must not be that he fiddled while the city was on fire but that he fiddled on the brink of hell.

You must forgive me for that crude monosyllable. I know that many wiser and better Christians than I in these days do not like to mention heaven and hell even in a pulpit. I know, too, that nearly all the references to this subject in the New Testament come from a single source, but then that source is our Lord himself. People will tell you it is St. Paul, but that is untrue. These are an overwhelmingly dominical doctrine.” That is, coming from the Lord Jesus.

“They are not really removable from the teaching of Christ or of his church. If we do not believe them, our presence in this church is great tomfoolery. If we do, we must sometimes overcome our spiritual prudery and mention them. The moment we do so, we can see that every Christian who comes to a university must at all times face a question compared with which the questions raised by the war are relatively unimportant.

He must ask himself how it is right, or even psychologically possible, for creatures who are every moment advancing either to heaven or to hell to spend any fraction of the little time allowed them in this world on such comparative trivialities as literature or art, mathematics or biology.

If human culture can stand up to that, it can stand up to anything. To admit that we can retain our interest in learning under the shadow of these eternal issues but not under the shadow of a European war would be to admit that our eyes are closed to the voice of reason and very wide open to the voice of our nerves and our mass emotions.”

In other words, so often when these questions are laid out in front of us our horizons are just too small. They’re just too little. We worry about the wretched devastation from a tsunami, and so we ought to worry. We worry about the wretched devastation caused by the equivalent of three tsunamis every year in Africa called AIDS, and so we ought to worry.

But it’s all nothing compared with the devastation coming from hell itself, for there is a heaven to be gained and a hell to be shunned, and we cannot even begin to think about these questions properly until we get those first two pillars rightly in place along with the four more still to come.

Join The Carson Center mailing list

The Carson Center for Theological Renewal seeks to bring about spiritual renewal around the world by providing excellent theological resources for the whole church—for anyone called to teach and anyone who wants to study the Bible. The Center helps Bible study leaders and small-group facilitators teach God’s Word, so they can answer tough questions on the spot with a quick search on their smartphone.

Click the button below to sign up for updates and announcements from The Carson Center.

Join the mailing list »Don Carson (BS, McGill University, MDiv, Central Baptist Seminary, Toronto, PhD, University of Cambridge) is emeritus professor of New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, and cofounder and theologian-at-large of The Gospel Coalition. He has edited and authored numerous books. He and his wife, Joy, have two children.